Turkish Airlines Flight 981 (TK981) was a flight from Istanbul-Atatürk (ISL) to London-Heathrow (LHR) with a layover at Paris-Orly (ORY). On March 3, 1974, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 crashed into the Ermenonville Forest, 37.76 kilometers (23.46 miles) outside Paris. The fatal crash, which killed all 335 passengers and 11 crew on board, was the deadliest plane crash in aviation history until March 27, 1977.

The Incident

The incident occurred at approximately 11:42 a.m. GMT on Sunday, March 3, 1974. The aircraft involved was a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 registered as TC-JAV, the owner and operator of Turkish Airlines (Türk Hava Yolları). The tragedy occurred at the Ermenonville Forest, a state-owned forest in Oise, France. The forest is famous for its moors, Scot pines, introduced in the 19th century, and sandy soil. One of the most precious ecological sites in Hauts-de-France houses a rare bird, the European nightjar, and a praying mantis.

The operation was a commercial flight, TK 981, with the route Istanbul-Orly-London. The aircraft commander was Nejat Berköz, and there were 11 crew members and 334 passengers. During the flight to London, when the aircraft reached 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) during the climb, the Air Traffic Control (ATC) realized there was a transmission into the Turkish language. The heavy background noise and the pressurization warning partially shadowed the talking noises, followed by an overspeed warning.

While the warnings went off, the aircraft radar return split in two, and the secondary radar label disappeared. Approximately seventy seconds after those indications, the aircraft, operating at high speed and with a small angle of descent, crashed into the treetops and broke into pieces in the forest. As a result, 346 people were killed, the aircraft was completely demolished, the cargo was destroyed, and certainly, the state forest land was damaged.

The Investigation

On March 4, 1974, the Minister for Transport appointed a six-person team as the Commission of Inquiry. The aim was to investigate the circumstances and the causes to curate a good approach to conclusions that should be taken from the accident. In compliance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation (which reflects the Standards and Recommended Practices covering Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation, defined according to certain categories), the State of Registry and the State of Manufacture, collaborating with technical advisers, contributed to the work of the Commission.

British and Japanese official observers were authorized along with the French and Turkish experts, FAA (Federal Aviation Administration, Mcdonall Dougal, Swiss Federal authorities, Swissair technical workshops, and the UK Accidents Investigation Branch sabotage expert.

The work done by the mentioned experts was not only for the accident site but also for the parts of the aircraft structure because some parts were first to become detached from the aircraft, where they were found 1.5 kilometers (0.93 miles) further below the aircraft's path.

The work concerned with:

- Study of the main wreckage and its main parts, the wreckage trail, and the transportation of the wreck to a lab for further examination and investigation of the documents related to the aircraft maintenance and its potential to operate after the loss of the aft cargo door.

- Information considering the history of the flight, including the voice recordings, air/ground communications, study of the radar films, and the flight path.

- Analysis of the data provided by the flight data recorder.

- Study of the wreckage found below the aircraft's flight path, 15 kilometers (9.32 miles) further back from the accident site.

- Examination of the bodies of the victims and the rescue operations.

The Flight

The aircraft landed at Orly at 10:02 a.m. local time as scheduled. On landing, there were 167 passengers on board. Fifty of them disembarked at Paris. The aircraft was parked on stand A2 at the Orly-Sud air terminal. Then, the plane was taken over by Turkish Airlines staff and airport service personnel. The aircraft was supplied with 10,350 liters of Jer A-1 fuel.

The scheduled stop was for an hour; however, it came up to one hour and a half because of the last-minute embarkation of numerous British Airways and Air Frane passengers. The door of the aft cargo compartment was secured and locked around 10:35 a.m. local time.

The read-out of the reported flight data recorder portrayed that when the aircraft started operating, it was carried out automatically by the flight control system. Three or four seconds before 11:40 a.m. local time on the cockpit voice recording, it is possible to determine the decompression noise. The co-pilot on the recording said, " The fuselage has burst," and the pressurization aural warning can be heard.

The controller, who was in course with the progress of TK 981, heard a transmission to the Turkish language, heavy background noise, and the pressurization warning, and then, the overspeed warning added to the already confusing sound environment.

Simultaneously, with the overspeed warning, the aircraft disappeared from the secondary radar scope. On the primary radar, the aircraft split in two, as stated in the final report of the Department of Trade Accidents and Investigation Branch. One part remained stationary at about 24 NM, bearing 45 degrees from Orly, which could be related to the parts ejected from the plane, and it persisted for two or three minutes.

The second part, the echo of the aircraft itself, followed a path that curved to the left. The Control received the chaotic transmission, and afterward, a fresh but short transmission was recorded on the ground. The final transmission was heard at 11:41 a.m., six or seven seconds past. The controller made many calls to TK 981 but received no answer.

There were 77 seconds between the decompression time and the impact with the ground. The aircraft crashed into the forest about 15 kilometers (9.32 miles) from the village of Saint-Pathus, where initial decompression and the first loss of parts of the aircraft occurred. The plane did not catch fire. The plane cut through the forest from east to west and caused great damage to the area 700 meters (2,297 feet) by 100 meters (328 feet). There were no survivors from anyone who was onboard; additionally, there were no occurrences of calls on the distress frequency.

Damage

Following the loss of the aft cargo door on the left-hand side and many parts of the aircraft, such as the floor and the seats, the plane broke into pieces with the impact of high-speed diving into the forest. 0.70 hectares of 20 to 30-year-old Scotch pines and 5.85 hectares of 50 to 70-year-old Scotch and maritime pines were damaged, resulting in around 220,000 Francs of loss.

The Crew

Nejat Berkoz was the Aircraft Commander of the DC-10-10 at the age of 44 at the time of the accident. He had 7,003 hours and 10 minutes of flight hours throughout his career. He transferred from the Turkish Air Force to Turkish Airlines and piloted F-27, DC-9, and DC-10. He had no prior accidents, and neither did the co-captain, Mr. Oral Ulusman. He was 38 years old and transferred from Turkish Air Force to Turkish Airlines, flying the same aircraft as Nejat Berkoz.

The flight engineer was Erhan Özer, the aircraft ground engineer onboard the aircraft was Engin Ucok, chief steward Hayri Tezcan, stewardesses Gülay Sönmez, Nilgün Yılmazer, Sibel Zahin, Semra Hıdır, Fatma Barka, Rona Altınay and Ayşe Birgili.

Rescue Operations

The accident occurred in two fatal phases, which left no chance of survival for the 346 people who were onboard. The first phase ejected six people at an altitude of 3,600 meters, and the second phase was the tragic crash into the forest.

Since the Air Traffic Control was aware of the situation because of the immediate loss of connection, locating the debris area was easy. After the information about the accident site had been determined and the message was transmitted, the first rescue team arrived a little more than half an hour after the crash. The first transmission of the deceased people was made to the church of Saint-Pierre de Senlis around 1:45 p.m. local time. The bodies near the villages of Saint-Pathus and Oissery were taken to Meaux Hospital.

Seventeen emergency centers with 56 various vehicles were utilized, and around three hundred people took part in the rescue operations on the first day. As for the final step, transferring the aircraft pieces began on March 8 and was completed on March 20.

Results of the Investigation

- The crew members were qualified, and there were no anomalies.

- The aircraft was certified, equipped, and operated compatible with national and international requirements.

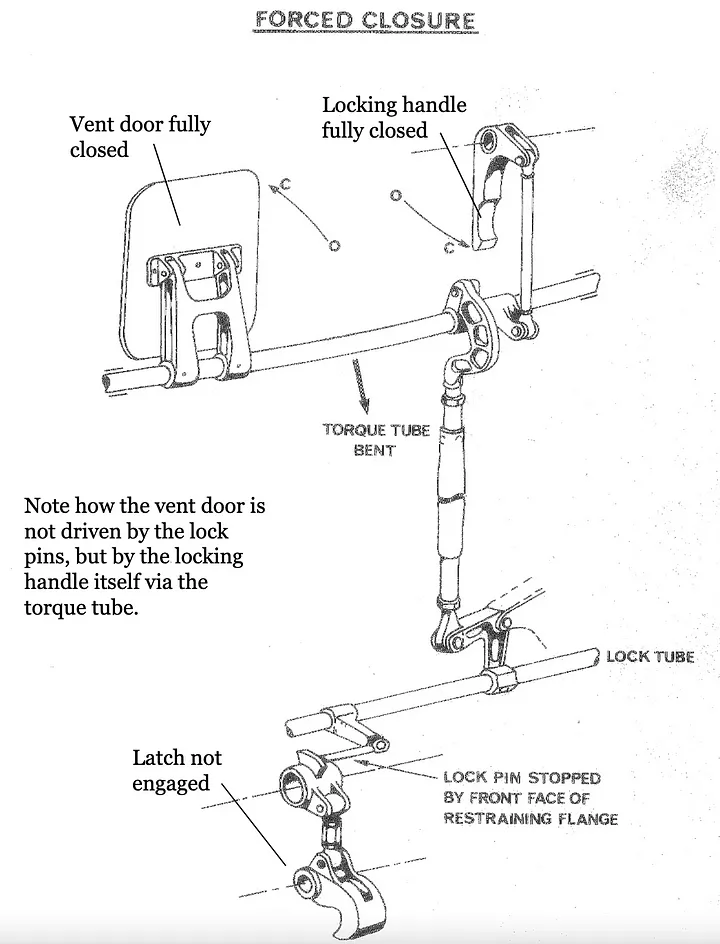

- Regarding the aft cargo door on the left-hand side, The support plate (Service Bulletin 52-37), which could assist in the case of incomplete engagement, was not installed pre-delivery and did not get detected. The modification aircraft went through after the delivery was not compatible with Bulletin 52-38. The adjustments of the lock pins and lock limit warning were not correct.

- During the layover at Orly, there were no visible indications that the aft cargo door was not secured.

- Around 12,000 feet, the door detached and caused an immediate pressure differential because of the pressure drop in the cargo compartment. It disrupted the floor and caused the ejection of 6 passengers, cabin seats, and other pieces.

- The deformation of the aircraft was caused by a false impairment of engine No. 2 and the flight controls. It was impossible to regain control.

- The door did not need any external immense force to unlatch because of the existing errors within its structure.

Because of the depressurization, there were disruptions to the floor where the cables ran, which resulted in damage and loss of control. So the accident resulted in incorrect latching of the aft cargo door before take-off, which put the aircraft in grave danger, leaving the crew nothing to do.

Aftermath

Issues related to the latch of the aircraft resulted from errors in interface design, human factors, and engineering responsibility. The failure of the door had been discovered in 1969 and resurfaced in 1970 while a ground test happened, both of which McDonnell-Douglas knew about.

McDonell-Douglas had ignored the concerns and considered it a small problem with a small possibility of an accidental event since if it had been taken seriously, the distribution of the aircraft would have taken time and would have disrupted the delivery schedule. This ignorance causes Dougsa to lose sales against the Lockheed L-1011 Tristar and the Boeing 747.

McDonell-Douglas faced multiple lawsuits from the victims' families. Their defense blamed the FAA for not issuing an airworthiness directive, Turkish Airlines for modifying the cargo door locking pins, and General Dynamics for an incorrect cargo door design. This did not end in the way the company wanted. McDonnell-Douglas and Turkish Airlines, with additional parties, settled out of court for an estimated $100 million in total, $80 million of the compensation being from McDonnell-Douglas, $18 million paid by its insurer Lloyd's of London.

After the tragic event, the latching system was redesigned to ensure the safety. Also, the FAA issued further changes with outward-opening doors, including DC-10, Lockheed L-1011, and Boeing 747. These changes aimed to prevent the catastrophic event of the cabin floor and other structures from getting damaged, which could result in losing control of the operation, as in Flight 981.

The accident was the deadliest plane crash at the time until the Japan Air Lines Flight 123 accident, which killed 583 people in total on December 8, 1985.

Maldivian Airlines Introduces First-Ever Widebody Aircraft, Plans New China Flights » Export Development Canada Secures Aircraft Repossession in Nigeria Under Cape Town Convention » Thousands of Flights Impacted as Winter Storm Blair Hits U.S. »

Comments (0)

Add Your Comment

SHARE

TAGS

STORIES Turkish Airlines Incident Turkey History Safety McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 Paris France CrashRECENTLY PUBLISHED

Could You Survive a Plane Crash? The Unlikely Science of Plane Crash Survival

With air travel consistently being heralded as the safest form of public transport, most of us do not board a plane pondering our chances of survival in the event of a crash. But, is it possible to survive one?

INFORMATIONAL

READ MORE »

Could You Survive a Plane Crash? The Unlikely Science of Plane Crash Survival

With air travel consistently being heralded as the safest form of public transport, most of us do not board a plane pondering our chances of survival in the event of a crash. But, is it possible to survive one?

INFORMATIONAL

READ MORE »

Maldivian Airlines Introduces First-Ever Widebody Aircraft, Plans New China Flights

Maldivian, the government-owned national airline of the Maldives, has just welcomed its first-ever wide body aircraft: the Airbus A330-200. With the new aircraft, the carrier also plans brand-new long haul international flights to China.

NEWS

READ MORE »

Maldivian Airlines Introduces First-Ever Widebody Aircraft, Plans New China Flights

Maldivian, the government-owned national airline of the Maldives, has just welcomed its first-ever wide body aircraft: the Airbus A330-200. With the new aircraft, the carrier also plans brand-new long haul international flights to China.

NEWS

READ MORE »

Thousands of Flights Impacted as Winter Storm Blair Hits U.S.

Winter Storm Blair has unleashed a huge blast of snow, ice, and freezing temperatures across the Central and Eastern United States.

As of Sunday afternoon, over 6,700 flights and counting have been disrupted. This includes cancelations and significant delays leaving passengers scrambling to change flights and adjust travel plans.

NEWS

READ MORE »

Thousands of Flights Impacted as Winter Storm Blair Hits U.S.

Winter Storm Blair has unleashed a huge blast of snow, ice, and freezing temperatures across the Central and Eastern United States.

As of Sunday afternoon, over 6,700 flights and counting have been disrupted. This includes cancelations and significant delays leaving passengers scrambling to change flights and adjust travel plans.

NEWS

READ MORE »